The lines, always precise, always intentional, always part of a disegno (project) are used to blur distinctions between the properly and the improperly architectural, shifting the emphasis from a language of forms to the performance of architecture’s materials in a seamless space. In the Capricci and in the Carceri the agility of his dynamic line blurs disciplinary and material divisions, questioning not only the validity of established and by then obsolete architectural languages, but the very nature of the “architectural”, producing unusual combinations of organic and inorganic, alive and dead, ephemeral and lasting, flesh and stone.

#Piranesi rome etching full#

Piranesi’s more creative works exploit to the full the possibility of the “material line” of the etching: no longer a tool of representation, here the line becomes a tool of design. But they also are, in and on the image that they produce: “material lines”, they have a physical presence, and possess specific spatial connotations that are linked to their medium. Lines of representation, they stand for something other than themselves - the shapes, contours and textures of an object and the effects of light - or are the record of a gesture, a passion, an emotion. Piranesi’s lines – meticulously drawn, precisely incised, lightly traced, nervously moving, smudged or erased – physically construct a space on the copper plate and then on paper.

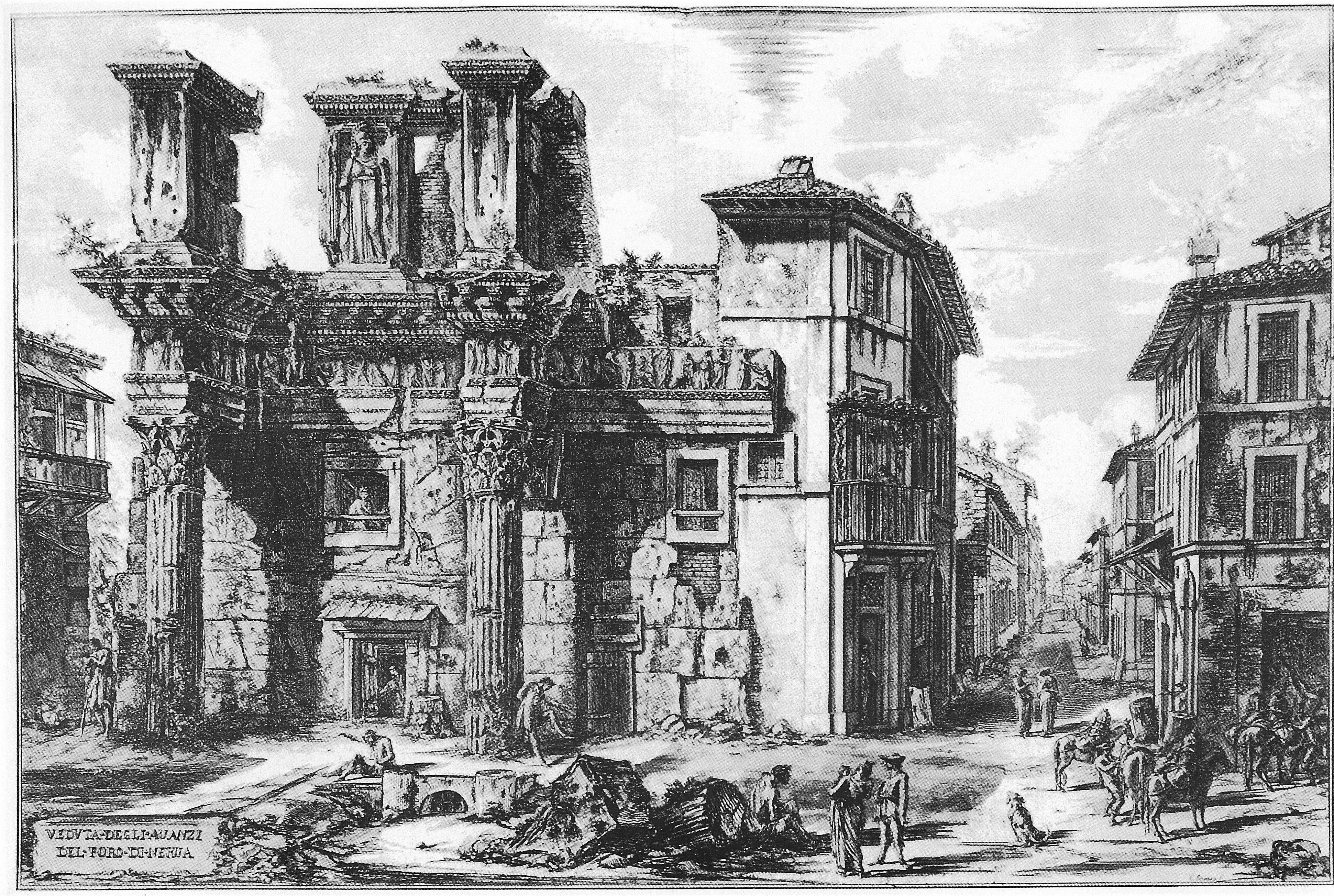

Images produced by lines are the space in which Piranesi operates as an architect, and what speaks to us today through the medium of etching are not only his archaeological surveys and reconstructions, and his views of ancient and modern Rome, but also – most crucially – the spaces of his invention. Etching opens also a new space for architectural creation, for a project of space that, while it remains untouched by use, change and life, will continue to communicate its ideas across time. Etching offers a medium to record and divulge the knowledge of ancient and modern architecture, which will last, he argues, longer than the subjects of its representations. Therefore, restoring Piranesi, his arguments, executed works and drawings to architectural history appear as a necessity.įor Giovanni Battista Piranesi one of the ‘more important’ things that the moderns invented is printing – and with it the reproducibility of drawings and architectural images. However, most of these evaluations lack a stable historical base. Piranesi’s perception caused him to be described as madman or idiosyncratic. Thus Piranesi placed Romans in another aesthetical category which the eighteenth century called ‘the sublime’. Secondly, he distinguished Roman from Grecian architecture identified with ‘ingenious beauty’. Concerning origins, he developed a history of architecture not based on the East/West division, and supported this by the argument that Roman architecture depended on Etruscans which was rooted in Egypt. Piranesi, however, conceived of these two debates as one interrelated topic. He has thus been excluded from the ‘story’ of the progress of western architectural history. Both of these served the identification of Piranesi as ‘unclassifiable’.

The former interpretation derived from Piranesi’s position on aesthetics, the latter from his argument concerning origins. The second is the mode of codification of architectural history. The vectors of approach yielding misinterpretation of Piranesi derived from two phenomena: one is the early nineteenth-century Romanticist reception of Piranesi’s character and work. But Piranesi was misinterpreted both in his day and posthumously. He is numbered foremost among the founders of modern archaeology. He posited crucial theses in the debates on the ‘origins of architecture’ and ‘aesthetics’. In the architectural, historical, and archaeological context of the eighteenth century, Italian architect Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778) played an important role.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)